Land/Sea Gallery

Click the thumbnails to see a larger version of the image and the image caption.

Traditional hedge laying skills have been lost but thanks to the work of the National Park Authority and schemes such as Tir Gofal and Glastir, there is support for farmers who want to restore hedgerows and other wildlife habitats on their land.

Links: Pembrokeshire Coast National Park - Traditional Boundaries Grant Scheme 2020/21

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park - Conserving the Park scheme.

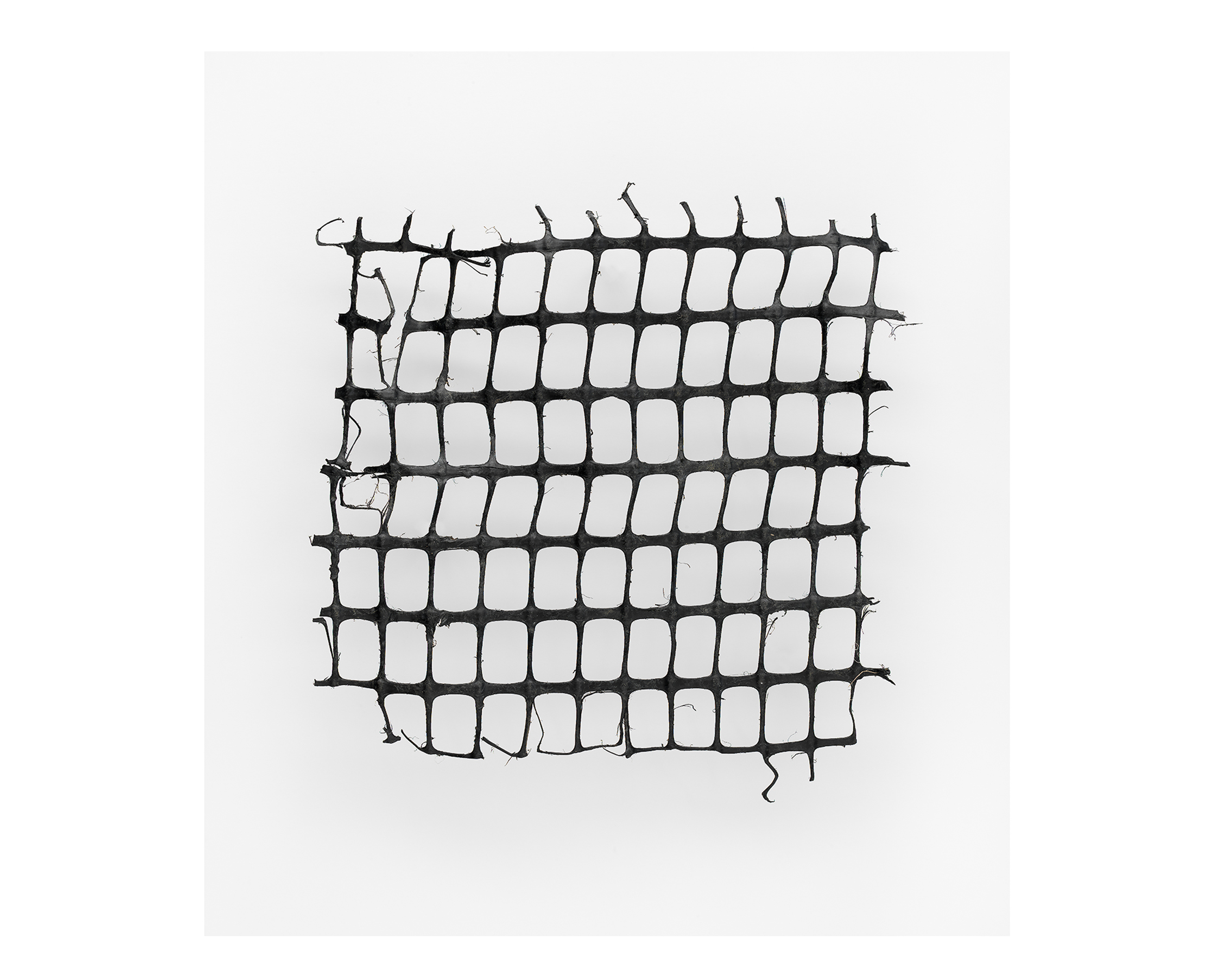

This melancholic moonlit photograph captures the dying branches of the ash trees surrounding the artist’s studio in North Pembrokeshire. Ash dieback is perhaps the epidemic that has gone unnoticed during the Covid-19 pandemic. Up to 95% of Britain’s ash trees could be lost to this disease. Pembrokeshire has been particularly hard hit.

This fungal disease, thought to have been introduced by commercial trade in saplings, is a reminder of the need to protect our habitats and ecosystems.

Passionate ecologists, committed volunteers and caring landowners are working hard to replant native woodlands and hedgerows.

Conifer plantations like this one in Scotland contribute to climate change because draining land for forestry releases the carbon stored in bogs. In Pembrokeshire, the National Park Authority bought a spruce plantation near the Gwaun Valley, and has started to restore it to moor and heathland. Now heather, bilberry and gorse are recolonising the landscape. Rare marsh fritillary butterflies live nearby.